Adolescence is a formative time of exploration, development, and multiple physical, emotional, social and psychological changes.

Emotional ups and downs are a normal part of life for anyone. However, during the teenage years they can be stronger and more frequent [1]. Fluctuating mood can be influenced by multiple different factors related to the various changes mentioned above, and are a sign that your child is trying to understand and navigate more complex emotions and experiences. Parents play an important role in supporting their children through this critical developmental stage. In fact, parents and friends are the main sources of support who teenagers turn to for help, so it’s worth being equipped for when they might need you [2].

Teenagers are sometimes described as being moody or temperamental, so how do parents know when there might be something more serious going on? Whether this is your concern or not, education and open communication with young people is important to help prevent harms, so this article will provide some pointers on how to have a conversation with your teen about mental health.

Firstly, let’s understand more about why teenagers may struggle more with changes in mood and mental ill-health. The release of hormones from the brain triggers the onset of puberty, which brings with it a diverse array of physical and biological transformations [3].

Physical factors:

Many physical changes occur during adolescence, both inside and outside of the body. This includes heightened growth and metabolic activity, changes in fat and muscle, and the development of breasts and genitals [3]. As your child’s body is changing, they may be feeling more self-conscious, especially if their development is happening earlier or later to their peers. This may also mean they’ll want more privacy.

Brain factors:

The brain undergoes both structural and functional changes during adolescence, and keeps developing into your 20s [1,3,4]. It releases a range of hormones which influence physical and sexual development, as well as “reorganising” the brain and its structure, and heightening emotional responses [5]. The prefrontal cortex of the brain is the last region of the brain to develop, and is associated with higher-order cognitive processes, decision-making and planning skills, as well as emotional regulation [4,6]. This may mean that emotional regulation may be harder for your teenager, and stronger emotional reactions may be more common. Impulsive and risky behaviours have also been linked to this prolonged development of the prefrontal cortex [1]. Another major brain change that occurs during adolescence is synaptic pruning, whereby unused connections are “pruned away,” and other connections are strengthened. This increases brain efficiency and contributes to the development of a more mature brain [7].

Social and emotional factors:

Along with changing bodies and emotions, social settings often change during this period of time, too. More time is often spent with peers over adults as your child is moving further towards independence, and there can be more tension between the child and parents [1]. This shift in social interactions can further contribute to the increase in emotional reactivity [1]. There is a lot to navigate as a teenager, and it is often a time when peer pressure is at its highest [8].

Reading up on mental health from sources such as this and this can help you to be better equipped to support your child. It can be useful to go through some resources together with your teen to help them better understand what they’re going through, too.

Some examples:

- The Big Six modifiable factors for youth mental health, from OurFutures

- Factsheet: Mental health and alcohol/drug use during the COVID-19 pandemic, from Positive Choices (offers support for looking after mental health, not just specific to Covid-19)

- Anxiety and how to manage it: pre-teens and teenagers, from raisingchildren.net.au

- Video: Why the teenage brain has an evolutionary advantage, from the University of California.

- Factsheet: The Teen Brain: 7 Things to Know, from the National Institute of Mental Health

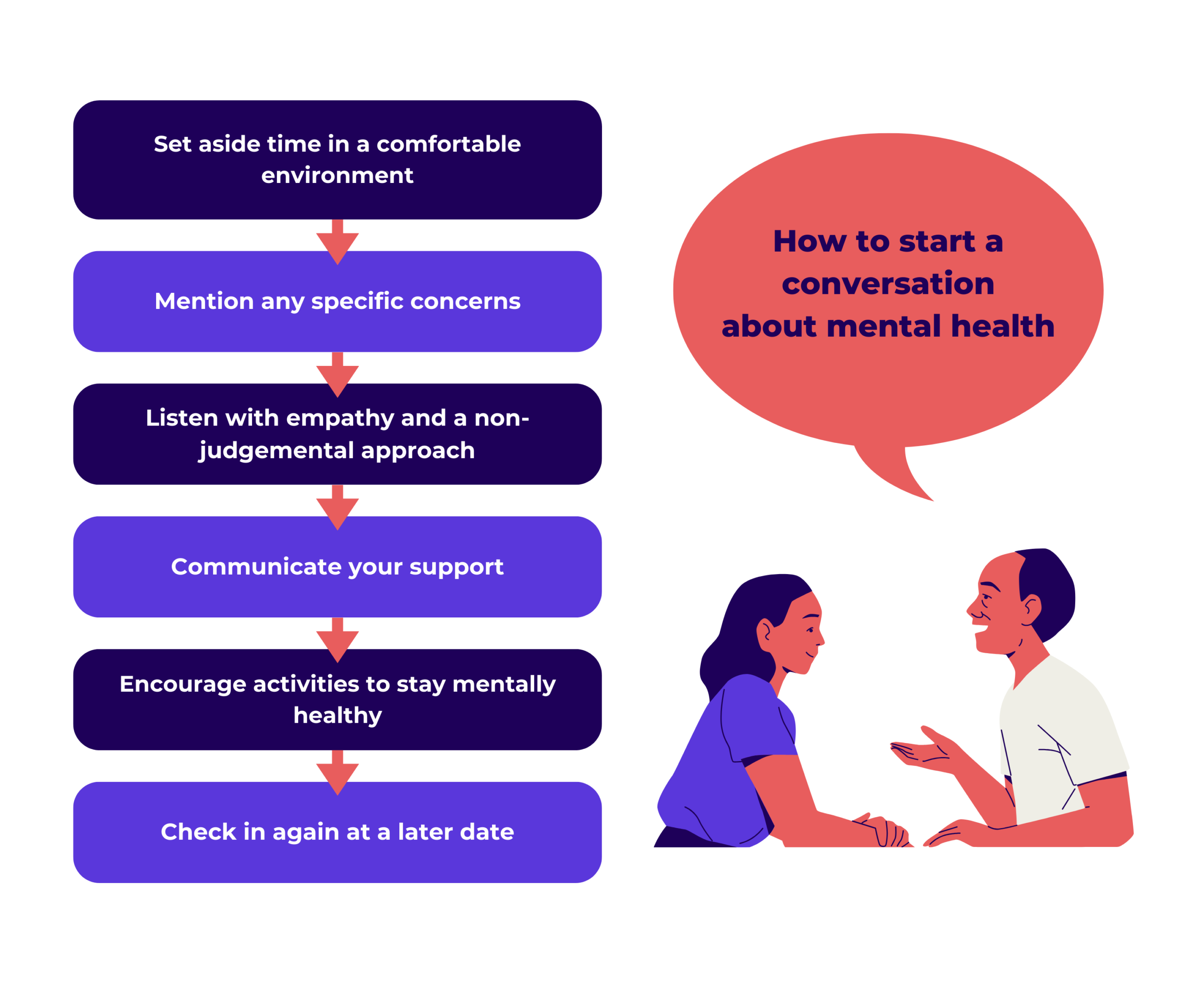

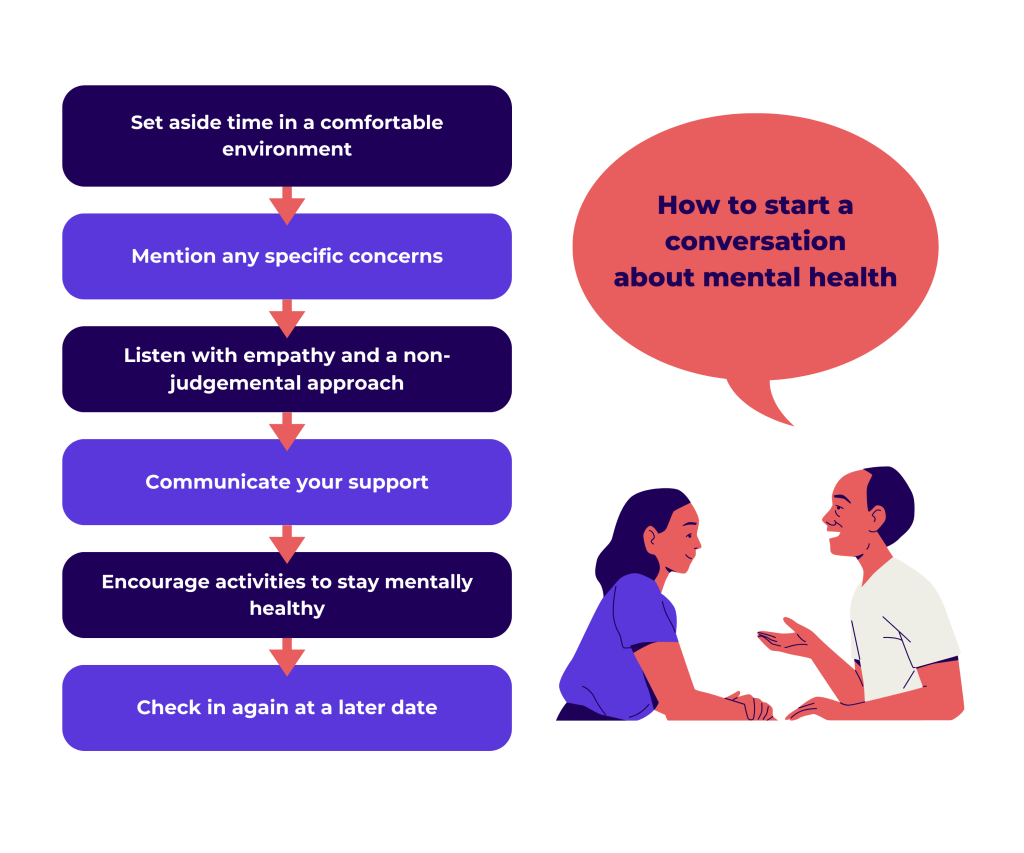

When you feel equipped, calm and ready for the conversation, set aside time to talk in a comfortable environment which feels safe and familiar to your teenager. Try and choose a time where they are calm and less likely to be distracted. You can also create opportunities for this, such as cooking dinner together or going for a quiet walk.

Bring up any specific concerns you have. You can start the conversation with open-ended questions such as:

- “I’ve noticed you seem quieter lately. How are you going?”

- “I’ve been noticing that you seem (sad/withdrawn/not yourself) lately. I am worried about you. Can we talk about it?”

Approach the conversation without judgement, and really take the time to listen to the young person with empathy. They are likely to be more receptive if it is a two-way conversation and they’re given the space and safety to express themselves. Avoid using judgemental language, such as labelling a behaviour as “wrong,” or “lazy.” It’s also unhelpful to make comparisons such as, “other people have it so much worse,” or remind them of the positives, as this can make them feel misunderstood and invalidated [9].

Communicate your support, and let the young person know you’re there for them. Talk to your teen to better understand what kind of support they want from you. They may not even know themselves, so it can be helpful to offer some suggestions.

You can ask questions such as:

- How can I best support you, right now and moving forward?

- Do you feel supported by your family and friends? If not, what would help you to feel more supported?

- Do you feel that you have people to talk to about these things/if you’re struggling?

- Do you ever feel like you need to talk to someone, but don’t know who to turn to?

- Do you feel like you have enough healthy coping strategies? What do these involve for you? And if not, do you have any ideas for some that could be helpful?

- I love and care about you. What’s the best way we can regularly check-in about these things?

Reassure them that solutions are possible, and that help is available.

Next, brainstorm and encourage activities to stay mentally healthy. Practicing healthy habits and being equipped with coping strategies is so valuable, as it’s not only helpful for prevention of mental ill-health, but means that we’re better prepared for it if a crisis does occur.

Some examples of activities could be:

- Making time to see family and friends

- Physical activity: going for walks or runs, swimming, yoga, or taking up a team sport

- Keeping a journal on thoughts and feelings to clear the head through writing

- Talk things through with a trusted friend or family member

- Getting a good night’s sleep

You can also make a list of “mood boosters” with your child, so they have a reminder of things that help them when their mood drops [10]. This can involve the activities above, as well as things like coming to you for a hug, watching a movie together, baking, listening to a favourite song or podcast, watching funny videos on YouTube, and so on. You can find more on strategies to support mental health . It’s important to note that for more serious mental ill-health, more intervention and strategies are needed.

Towards the end of the conversation, ask your teenager if you can check-in with them again another time soon. These conversations are ongoing, and it’s helpful for the young person to know you’re consistently there for them to talk to.

Finally, remember to consider the whole child when talking about youth mental health. Being aware of the many different influences and interactions going on in their world can help you better understand your child and their experience.

Image inspired by Beyond Blue and Emerging Minds.

If you think your teen may need professional help, you can suggest they speak with a counsellor or GP. This may be needed if they seem particularly distressed, or their struggles are notably impacting their usual activities (they may be withdrawing or avoiding school, family and social life, or other activities). There are plenty of other support services, such as:

Kids Helpline

1800 55 1800

Beyond Blue

1300 22 4636

Headspace

See more on our mental health course for high school students here.

Author: Francesca Wallis.

With expert review by researchers at the Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use.

References:

[1] B. J. Casey, R. M. Jones, and T. A. Hare, “The Adolescent Brain,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1124, no. 1, pp. 111–126, Mar. 2008, doi: https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.010. [2] “Most teenagers turn to parents and friends for help,” aifs.gov.au, Nov. 2018. https://aifs.gov.au/media/most-teenagers-turn-parents-and-friends-help [3] N. Vijayakumar, Z. Op de Macks, E. A. Shirtcliff, and J. H. Pfeifer, “Puberty and the human brain: Insights into adolescent development,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 92, pp. 417–436, Sep. 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.06.004. [4] “The Teen Brain: 7 Things to Know,” National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2023. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/the-teen-brain-7-things-to-know#pub4 [5] P. Vigil, J. P. del Río, B. Carrera, F. C. Aránguiz, H. Rioseco, and M. E. Cortés, “Influence of Sex Steroid Hormones on the Adolescent Brain and Behavior: An Update,” The Linacre Quarterly, vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 308–329, Aug. 2016, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00243639.2016.1211863. [6] W. R. Hathaway and B. W. Newton, “Neuroanatomy, Prefrontal Cortex,” PubMed, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499919/ [7] L. P. Spear, “Adolescent Neurodevelopment,” Journal of Adolescent Health, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. S7–S13, Feb. 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.006. [8] L. Steinberg and K. C. Monahan, “Age differences in resistance to peer influence.,” Developmental Psychology, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1531–1543, Nov. 2007, doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531. [9] L. Birrell, A. Baillie , E. Kelly, and M. Teesson, “I think my teen is depressed. How can I get them help and what are the treatment options?,” The Conversation, Oct. 04, 2023. Accessed: Oct. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://theconversation.com/i-think-my-teen-is-depressed-how-can-i-get-them-help-and-what-are-the-treatment-options-206702 [10] “Moods: helping pre-teens and teens manage emotional ups and downs,” Raising Children Network, Oct. 20, 2022. https://raisingchildren.net.au/pre-teens/mental-health-physical-health/about-mental-health/ups-downs#emotional-ups-and-downs-why-they-happen-nav-title (accessed Mar. 26, 2024).