What do we really mean when we say that the OurFutures programs are evidence-based and clinically proven? These could come across as buzzwords to some, but the amount of work that goes into the research behind our programs to make them evidence-based is often underestimated or misunderstood.

So, let’s delve a little deeper into what it means for our health education programs to be evidence-based, using the example of our current vaping trial.

Our research comes out of The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use at the University of Sydney. The OurFutures model (formerly known as Climate Schools) was developed over a decade ago by Professor Maree Teesson and Professor Nicola Newton, along with their research colleagues Dr Lauren Gardner, Dr Katrina Champion, Dr Amy-Leigh Rowe, and Lyra Egan, who are driving the research today. The researchers at The Matilda Centre identified the need for scalable, school-based prevention education programs with long-term proven efficacy. OurFutures is innovative in that it utilises a harm-minimisation and social influence approach to substance use prevention and overcomes implementation barriers that often arise in school-based programs [1]. Over a decade of research has been dedicated to establishing the efficacy of the OurFutures programs, involving focus groups, pilot studies, and 8 large randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including >21,000 students from 240 schools across Australia. The main outcomes of these RCTs are then published in leading peer reviewed academic journals, and the programs are made available to all schools once proven effective. This process takes years of hard work, planning, and dedication.

What does “evidence-based” really mean?

To say that a resource is “evidence-based” means that it is backed by scientific evidence. The type and level of evidence that supports a particular resource may vary. In the case of the OurFutures modules, “evidence-based” means that the information provided comes from reliable sources, has been reviewed by health and education experts, and is evaluated in rigorous scientific research studies.

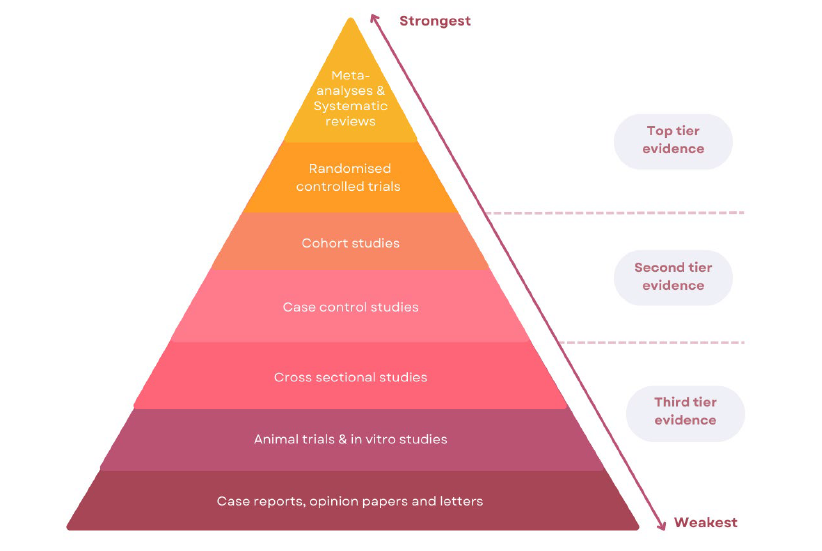

Levels of evidence

There are many different study designs, such as RCTs, case reports, animal trials, cross sectional studies, case control studies, and cohort studies. However, these are not all created equal.

Figure adapted from Hattis [2]

What does scalability mean?

The OurFutures programs were developed to address the need for scalable prevention approaches; most recently, to address the urgent need to prevent e-cigarette use. In this context, scalability refers to a health intervention that has shown to be effective on a smaller scale under controlled conditions (ie. in an RCT), still being effective when extended into real world conditions that reach a larger proportion of the eligible population [3].

The OurFutures vaping trial

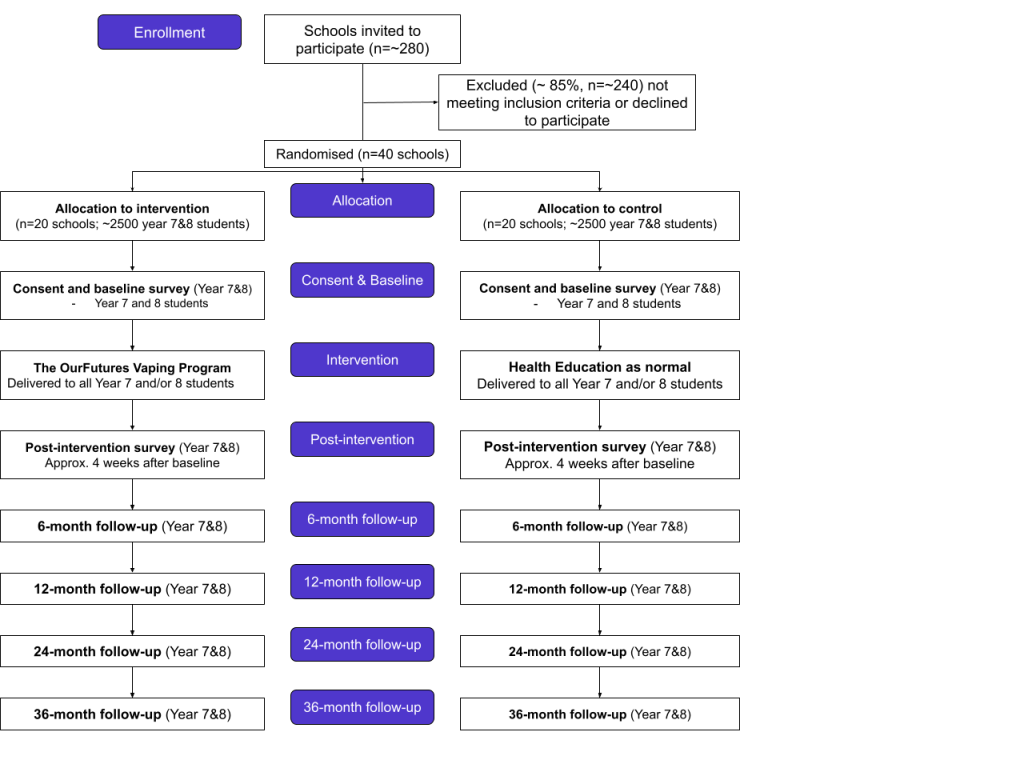

The OurFutures vaping trial is a cluster RCT of a school-based eHealth intervention to prevent e-cigarette use among adolescents. We are running a large multi-site trial to evaluate the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the intervention among year 7 and 8 students in 40 schools across New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia. The program consists of four online cartoon lessons and associated activities delivered during health education classes [1].

Throughout the design phase, students and teachers were consulted to build character profiles and storylines for the cartoons and ensure the program was feasible, and appropriately aligned with the latest evidence and health education curricula. This involved student surveys, focus groups, interviews, and feedback from end-users through multiple public webinars, school presentations and Q&A sessions [1].

In the trial, schools are randomly assigned to either the OurFutures Vaping Program intervention group or a control group that receives health education as usual. The schools in the OurFutures Vaping group will receive four weeks of web-based cartoon lessons and accompanying activities during health education classes. While the program predominately focuses on e-cigarette use, it simultaneously addresses cigarette smoking. Students provide informed active consent and parental consent to participate. Baseline data is then collected through self-report surveys to identify the starting points for which future data will be compared against (at 6-, 12-, 24-, and 36-months after baseline) [1].

The trial will assess whether students who receive the OurFutures Vaping Program have reduced uptake and use of e-cigarettes, compared to students in the control group. It will also assess any differences in use of tobacco cigarettes, knowledge relating to e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes, attitudes and beliefs about e-cigarettes, resource use, and mental health. If effective, the intervention will be available to schools through the OurFutures platform, having the potential to make a substantial health and economic impact to Australia.

What is a two-arm cluster randomised controlled trial?

Randomised controlled trials are the gold standard for efficacy research. RCTs reduce biases and are the most rigorous and reliable strategy to determine the cause-effect relationship between an intervention and an outcome [4]. A cluster randomised controlled trial (also known as a group randomised trial) is simply an RCT which randomises groups of individuals (or ‘clusters’ – in our case schools) [5]. Cluster randomisation at the school level is used in the vaping study to avoid potential contamination of the control group by the intervention group [1].

Subjects (or schools in our case) are randomly assigned into groups. Automatic randomisation is used to remove researcher involvement. In the case of our vaping trial, there are two groups (ie. two arms): the control group (health education as usual) and the intervention group (OurFutures Vaping Program).

Below is an overview of the recruitment and randomisation process for the OurFutures Vaping trial [1]:

After a long development process, RCTs are used to ensure the results are reliable and unbiased. Although they are time-consuming and costly, RCTs generate findings closer to the true effect than other study designs, due to the minimised risk of confounding variables influencing results.

The rigorous research behind the OurFutures modules has also demonstrated the long-term effects of our interventions. For example, the first clinical trial that showed efficacy for the OurFutures alcohol module (then known as Climate Schools) was published in 2006 [6]. Three more studies were then undertaken: two in 2009 and one in 2012, which showed the alcohol module to be an effective intervention in increasing alcohol knowledge and reducing alcohol use, as well as overcoming implementation barriers [7-9]. In 2021, a 7-year follow-up study was published, which demonstrated the long-lasting effects of our school-based interventions in reducing risky drinking and related harms into adulthood [10].

For more information on the evidence and a list of all the studies for each OurFutures module, head here.

In summary, evidence-based refers to an approach that is grounded in strong scientific evidence and research. The OurFutures programs are developed based on the best available evidence and evaluated in meticulously designed studies. The use of evidence-based practices ensures that our interventions are reliable, and are clinically proven to make a long-lasting positive difference in the lives, health and futures of our youth.

More background information about the OurFutures Vaping trial and study protocol can be found here.

Author: Francesca Wallis

References:

[1] L. A. Gardner et al., “Study protocol of the Our Futures Vaping Trial: a cluster randomised controlled trial of a school-based eHealth intervention to prevent e-cigarette use among adolescents,” BMC Public Health, vol. 23, no. 1, Apr. 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15609-8.[2] Hattis, D., Options for basing Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) on chronic disease endpoints: report from a joint US-/Canadian-sponsored working group – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. 2016. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Hierarchy-of-evidence-pyramid-The-pyramidal-shape-qualitatively-integrates-the-amount-of_fig1_311504831

[3] Milat AJ, King L, Bauman AE, Redman S. The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promot Int. 2013 Sep;28(3):285-98. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar097. Epub 2012 Jan 12. PMID: 22241853.

[4] E. Hariton and J. J. Locascio, “Randomised Controlled Trials – The Gold Standard for Effectiveness Research,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, vol. 125, no. 13, p. 1716, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15199.

[5] “What is a CRT? | Cluster Randomised Trials,” Queen Mary University of London. https://clusterrandomisedtrials.qmul.ac.uk/what-is-a-parallel-crt/

[6] Vogl, L. E., & Teesson, M. (2006). The efficacy of a computerised school based prevention program for problems with alcohol use: Climate Schools. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 198A.

[7] Vogl, L., Teesson, M., Andrews, G., Bird, K., Steadman, M., & Dillon, P. (2009). A computerised harm minimisation prevention program for alcohol misuse and related harms: randomised controlled trial. Addiction. 104, 564-575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02510.x

[8] Newton, N. C., Vogl, L. E., Teesson, M., Andrews, G. (2009). Climate Schools: Alcohol module: Cross-validation of a school based prevention program for alcohol misuse. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 201-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802653364

[9] Vogl, L.E., M. Teesson., Newton, N. C., & G. Andrews. (2012). Developing a school-based drug prevention program to overcome barriers to effective program implementation: The CLIMATE schools: Alcohol module. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2, 410-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2012.23059

[10] N. C. Newton et al., “The 7-Year Effectiveness of School-Based Alcohol Use Prevention From Adolescence to Early Adulthood: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Universal, Selective, and Combined Interventions,” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 520–532, Apr. 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.10.023.